0

A Whisper of Superstitions

In Abruzzo’s mountain villages, the Ognissanti wind carries the scent of roast chestnuts and new olive oil, fermenting grapes and bitter stufa smoke, bells tinkle, and, hung on strings on door frames, churches, sheep, and cows are superstitiously thought to ward off evil. Giovanni Pansa’s 1924 classic, Myths, legends and superstitions of Abruzzo (Miti, leggende e superstizioni d’Abruzzo), described a world where faith and fear mingled, with saints, witches, bread dough, and girls, as well as lunar cycles, were tied to superstition.

A century later, those beliefs still ripple quietly through kitchens, fields, and fire festivals. Here are twelve tales, fragments of memory and magic that still shape how many Abruzzesi understand luck, protection, and the unseen that travelled far with families to new shores and continents.

Women & the Moon: Blood, Bread, and Taboo

Pansa wrote that in villages like Guardiagrele and Anversa degli Abruzzi, a woman’s menstrual cycle was “a tide of the moon,” powerful, natural, but best handled with care. During menstruation, women were told not to bake bread, as the dough would not rise; not to stir wine or tomato passata in case of a vigorous ferment; and to avoid making cheese, as milk would curdle.

Pansa’s village notes echo a much older Mediterranean idea. Pliny the Elder wrote in his Natural History that contact with a woman’s “monthly flux” could turn new wine sour, make crops barren, kill grafts, dry seeds, dull steel and ivory, rust iron and bronze, and even drive dogs mad. In the same work, he claimed a menstruating woman could dispel caterpillars and crop blights simply by walking the field. This paradox treated menstrual power as both dangerous and protective.

These Roman notions saw blood and fermentation as volatile forces best kept apart. Some women tied a red ribbon around the wrist to “bind the blood.” Others waited for the new moon before returning to the kitchen, aligning their bodies with the rhythms of nature itself. Teenage girls in Canada, America, and Australia whose Abruzzesi parents still planted by the moon realised quickly it was an easy way to excuse themselves from chores!

Eyes, Shadows & Spirits

1. Malocchio – The Evil Eye

“One look of envy,” wrote Pansa, “can wilt a harvest.” To diagnose it, olive oil is dropped into a bowl of water: if the drops spread, the eye has struck. The cure? Whispered prayers, coral horns, and a thread of red tied to the wrist or crib.

TR

Throwing salt with the left hand or making the “horns” gesture to repel bad luck is a daily superstition in many kitchens even now.

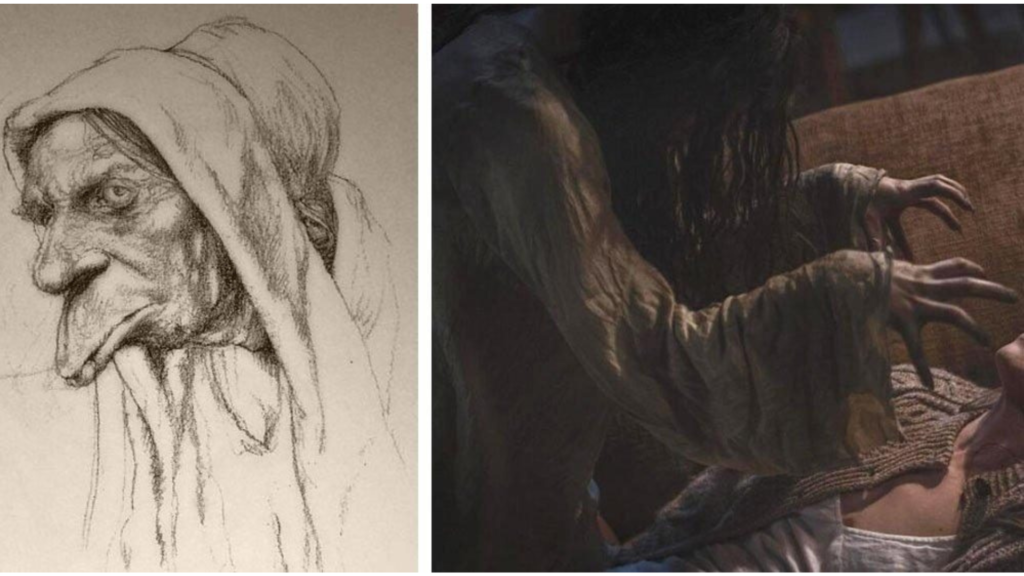

2. Le Streghe – The Witches of Abruzzo

Witch stories cling to the Monti della Laga. Discover Teramo recalls tales of women who rode night winds or slipped through keyholes to steal a sleeper’s breath. In Castel del Monte, the Italian Tribune tells how families burned a child’s clothes after nine nights of unexplained illness, the only cure for the witch’s curse.

To keep witches away, villagers scattered broom bristles or grains of salt on doorsteps. The witches, compelled to count, would be trapped until dawn. Yet in Pansa’s telling, these figures were often lonely women, feared, yes, but also pitied, misunderstood healers caught between worlds.

Abruzzo had its fair share of witch trials, most notably Angela Occhio d’Vrocca in Chieti, accused of casting spells on her daughter’s lover Ignazio Rapattuni, whose hen-like eyes were reported enough to make her a witch.

3. La Pandaféce – The Night Hag

In Abruzzo’s dialect, pandaféce names the spirit that presses on your chest at night — part witch, part cat. “It is a weight that steals your breath,” Pansa wrote. The remedy was simple: prop a broom upright or scatter sand by the bed, so she wastes the night counting.

Even now, when someone wakes from sleep paralysis, they might mutter, “Era la pandaféce” – it was the hag.

4. Il Mazzamurillə – The House Sprite

This tiny, troublesome house spirit or elf (think a naughty Dobby in Harry Potter) hides keys, tangles thread, and knocks at night. Leave him a saucer of milk and he’ll calm down; ignore him and he’ll braid the donkey’s tail. Some say he’s the ghost of an unbaptised child, others a leftover Roman household god.

A few families still pour out a drop of milk “for luck” on All Souls’ Night, not for cats, but for company.

Shape-Shifters, Signs & Fateful Nights

5. Lupo Mannaro – The Werewolf

In the Marsica and Chieti hills, villagers once warned of men cursed to roam as wolves beneath a full moon, a punishment for those born on Christmas Eve or failing to fast. The cure was to call the person’s name three times or mark them with iron.

The werewolf, like the witch, symbolised the wild edge of humanity, the fear of losing oneself to nature and of yielding to one’s instincts. Read the story of werewolves bathed in Collelongo’s fountain.

6. Segni & Presagi – Omens

Owls on a window meant death; dropping bread meant quarrels; stepping out with the right foot first brought luck. And while the world dreads Friday the 13th, Abruzzo’s unluckiest day is still Tuesday the 17th. English speakers are used to touching wood for luck; in Italy, it’s iron, preferably a horseshoe, to repel the devil – every day rituals against life’s minor uncertainties.

7. Fortuna Improvvisa – Sudden Good Luck

Sometimes fate smiled without warning: bird droppings on your shoulder, ants on your clothes, a twitching right eye, all lucky signs if met with good humour. To “lock in” fortune, villagers crossed themselves or whispered a quick thanks to St Nicholas.

Saints, Waters & Births

8. Serpenti & San Domenico – Cocullo’s Holy Snakes

Each May in Cocullo, devotees still drape live snakes over the statue of San Domenico. The Strada dei Parchi website recalls that shepherds once wore the saint’s medal to ward off bites and protect their flocks. It’s both Christian and pagan: purification and awe entwined.

9. Acqua Fortunate – Blessed Waters

On the night of St John the Baptist, Abruzzesi gather herbs and water before dawn. According to Strada dei Parchi, egg whites left in moonlight form ship-like shapes in the morning, an omen of safe voyages or family peace. Bathing at sunrise in rivers or the sea cleanses and renews.

A baptism of summer, equal parts magic and faith.

10. Nascite Speciali – Fateful Births

Children born with a caul, or on certain feast days, were destined for luck or second sight. Midwives preserved the caul as an amulet or discreetly burned it for protection. A red ribbon on the cradle guarded against jealousy and the malocchio.

Talismans, Knots & Threads

11. Talismani Contadini – Peasant Charms

Coral horns, wolf teeth, and saint medals hung on animals and children alike. In Teramo and L’Aquila, small iron keys were woven into cords for newborns – unlocking luck.

Protection was portable, practical, and often beautiful. View Adrianna Gandolfi’s extraordinary paper to see the full range – Amulets, Magical Ornaments from Abruzzo.

12. Nodi Magici – Knots & Bindings

A strand of red thread, tied nine times, could bind a lover’s affection or, misused, cause harm. To break such knots, prayers were whispered as they were untied.

The belief mirrored Abruzzo’s textile craft traditions: weaving fate one loop at a time.

Belief as Care

From witches in the Laga Mountains to milk left for house spirits, Abruzzo’s superstitions reveal how the region’s population managed people and things beyond their control. Pansa ended his 1924 study in Abruzzo with “It is better to believe a little, and laugh a little, than to believe in nothing at all.” Perhaps a century later, we should concentrate on how we can laugh a little more if we don’t adopt another man’s means to control things beyond his control.

Sources & Further Reading

- Giovanni Pansa, Miti, leggende e superstizioni d’Abruzzo. Studi comparativi, Vol. I (Lanciano: Rocco Carabba, 1924)

- Ubaldo Caroselli, Superstizioni e credenze popolari in Abruzzo (1927)

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Book 28 — on the powers of menstruation; Loeb Classical Library

- Chavarria, S. “Menstrual Blood: Uses, Values, and Controls in Ancient Rome,” Mondes Anciens (2022)

- Discover Teramo: Histories of Witches and Ancestral Fears on Monti della Laga

- The Italian Tribune: Witches of Abruzzo

- Strada dei Parchi: The Magical Night of St John the Baptist

- CityRumors: Superstizioni Abruzzesi